Q&A with Ali Awad, journalist/activist from Masafer Yatta

In which Ali tells us about recent events on the ground in Masafer Yatta, the Israeli High Court decision approving forced transfer of 1000+ Palestinian residents, as well as his thoughts on Zionism

Ali Awad is a 24-year-old journalist/activist from the small shepherding village of Tuba, located in the portion of the Masafer Yatta region of the occupied West Bank that the Israeli military declared several decades ago to be a live-fire training zone. He is also a friend of mine whom I met while participating in Hineinu from the Center for Jewish Nonviolence, an intensive solidarity project for Diaspora Jews interested in supporting the Palestinian civil resistance.1

In my conversation with Ali—recorded on May 15th, the day commemorating the Nakba, or catastrophe, that befell Palestinians in 1948—I started off by asking Ali to orient us to his daily life under military occupation. We then discussed recent events on the ground as well as Ali’s views on nonviolence, (anti)Zionism, and what a liberated, decolonized Israel/Palestine will look like.

The following has been edited for clarity and length.

Imagine that we’re in front of an audience of people who don’t know much about Israel/Palestine and please tell them about where you’re from and what it means to live under military occupation.

I am from the village of Tuba, located in Masafer Yatta, south of the city of Hebron in the West Bank, exactly where the West Bank meets the Negev Desert. I was born and raised in this area.

What’s it like living under occupation here? First of all, I am not allowed to build or have any kind of infrastructure. My village is located in Area C of the West Bank. The Oslo Accords [negotiated by the Israeli government and the Palestinian Liberation Organization during the 1990s as a supposedly temporary arrangement on the way to a final settlement] classified 60% of the West Bank as Area C. Here the Palestinian population and their land are totally under the Israeli military control.

My village existed for decades before the Israeli occupation—before 1967. If we want to build, we must receive a master plan from the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA), the branch of the Israeli military that controls the Palestinians living in Area C. Unfortunately, more than 98% of these master plans submitted to the ICA are rejected.

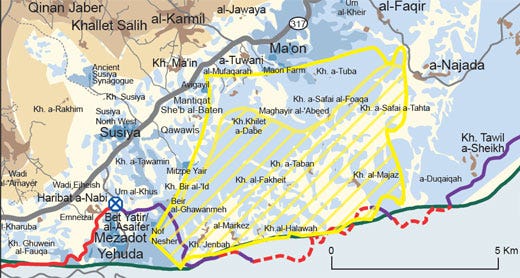

What does it mean to be under military occupation if the master plan of your village is rejected? Any kind of infrastructure or building inside your village is considered illegal by the ICA and is subject to demolition. In the whole area of Masafer Yatta, including my village and 11 other villages—35,000 dunams of lands [over 8,600 acres]—1000s of people are living without the ability to build anything in their village. For example, the road that connects my village and the other villages located in my area, are extremely poorly maintained dirt roads, which most cars can't drive on. We are not connected to water or electricity. Our homes are not like other homes that exist in any place where housing is permitted. They are small houses built very simply [many supplied by international humanitarian organizations].

We live our entire lives in these houses with the fear of being demolished—imminent demolition—at any point. In these villages around my home, there are weekly demolitions of at least 10 structures.

And while the Israeli army is trying to destroy our entire life, on the other side, Israel is developing and improving the Israeli settlements and outposts. After 1967, the Israeli military built army bases on the hills around my home. And in the early 80s, they transformed these military bases into Israeli settlements, taking tens of thousands of dunams of Palestinian land for the purposes of Israeli settlement. The Palestinian fields that used to be for grazing and cultivation now have settlements built on them, surrounded by fences.

These are the settlements. There are also the outposts [illegal under both Israeli and international law]. The land upon which settlers build their outposts becomes forbidden to Palestinians; but not just the land of the outpost itself, but all the areas surrounding it. If Palestinians go there, they will be attacked by settlers and be subjected to aggression from the military.

The main law that Israel is using in Masafer Yatta, and other areas of the West Bank, for the expansion of outposts is called the State Land Law, an outdated Ottoman law from 100 years ago. The law says if you don't use your land for three years, it reverts to the state for public use. Now Israel is using this law in order to expand the outposts and seize more land from the Palestinians. So if the Palestinians were not able to use their land for three years, the military occupation will declare it as state land, and then the State of Israel has the right to lease it for the settlers. So the settlers will build an agricultural outpost, then later it will become a settlement. The settlers from these agricultural outposts are mainly shepherds who have flocks, and they use their flocks to destroy the crops of the Palestinians.

So the areas declared as a state land next to these outposts are off-limits to the Palestinians. If a soldier catches Palestinians grazing there, even if the spot is five meters away from his home, the army will arrest them.

It feels like it was a long time ago that you and I were sitting in Basil Adraa’s guesthouse strategizing about how to respond to the Israeli High Court decision, but actually it’s only been 10 days since I left. Can you tell me what's happened in the last 10 days or so?

Recently, the Israeli army has been setting up “flying checkpoints” on the roads leading to the villages of Masafer Yatta, interrogating everyone that enters, including residents. Flying checkpoints aren’t new here, but the increased number of the flying checkpoints and military patrols on the roads really scares me because I fear that the eviction might not be in the form of putting people on trucks, as it happened before, but may be in the form of not allowing the people to access their villages. The people of Masafer Yatta have to go to the city of Yatta in order to get their medical treatment and purchase food. And if the people go to the city and cannot come back to their villages, this is also a scary policy that the Israeli military will use in order to block Palestinians from Masafer Yatta.

We are also seeing more military raids in the area. Yesterday, a group of soldiers raided the village of Tabaan, one of the eight villages in Masafer Yatta that’s under imminent threat of evacuation, for no clear reason. The soldiers attacked a family’s home, assaulted the mother, arrested the father and one of the sons, and confiscated their car. This is the kind of policy that people are facing increasingly after the High Court decision.

Additionally, people in the area are also organizing a response to this decision, mainly by trying to gain solidarity from the international community, activists from all over Palestine, as well as Israeli activists.

(You can participate in this international solidarity campaign by writing to your U.S. Representatives and Senators today.)

Last Friday, Palestinian activists and solidarity groups came to join a protest against the High Court decision organized by the residents of Masafer Yatta. We had planned to meet up on the road leading to the illegal Israeli outpost of Mitzpe Yair. This settlement, as well as several others, is located inside the firing zone [i.e., Firing Zone 918], but Israel does not plan to evacuate Mitzpe Yair like it plans to evacuate the Palestinian villages. In fact, Mitzpe Yair has a paved road that leads to it. It is connected to the electrical and water grids. Building inside the outpost—which is illegal even under Israeli law—has never resulted in a demolition order from the Israeli forces. Furthermore, these outposts—like Mitzpe Yair, Avigail, Havat Maon—are the main source of violence and terrorism against Palestinian living in the area. Settlers have placed large rocks on the road which passes by Mitzpe Yair on the way to Beir al Eid and Jinba, two Palestinian villages in the so-called firing zone. Palestinian residents need this road in order to reach the city for their medical and food needs. It’s the only path. And it’s not a path paved like the one that leads to the outposts. It’s a dirt road full of potholes. However, it’s the only option for the Palestinians, and settlers have blocked it with rocks so that no cars can pass. So organizers planned to demonstrate nonviolently in order to reach the outpost, remove the rocks, and show the racism of how the Israeli government implements that law.

Unfortunately, Israeli forces prevented many of the activists from reaching the site of the planned demonstration. More than 500 people had planned to show up and stand with the residents of the villages facing forced removal, but Israel suppressed them. Half of the buses were stopped inside Israel before the checkpoint between Israel and the West Bank. 120 people were stopped just five kilometers away, near the village of Tuwani.

The 100 people who managed to reach the road [to Mitzpe Yair] decided to at least remove the rocks. Before anything started, one Israeli woman, maybe in her late 60s, was just talking with a policeman and he pushed her and caused a fracture in her body. When we tried to open the road, one soldier stepped on one of the rocks in order not to prevent the protesters from removing it.

The Mitzpe Yair settlers responded with violence. I was there and I saw one masked settler wearing brass knuckles hanging out next to a soldier, throwing stones at the protesters. The soldier did not do anything to him.

If I am a soldier and I am supposed to do the law, I would see that a masked person with a weapon has the intention to attack other people in the area. And I am, as a soldier, the one who is supposed to ensure the security of everyone. Unfortunately, we were not able to manage even to remove the stones, because the army pushed us back and the settlers threw stones at us. Two of my friends were pushed to the ground next to soldiers by settlers. Another one of my friends, who is a resident of Masafer Yatta, was sitting on a rock, when this masked settler that they have mentioned before with the brass knuckles, punched him in the face of my friend, causing a fracture in his nose, and bleeding from the mouth, and a wound across his face. The settler was not arrested. He just walked away, hanging out, and standing next to the soldiers. The ambulance took my friend away to the hospital so that he could receive first aid.

Why is it that the Israeli military and police treat Jewish Israeli settlers one way and Palestinian residents another way?

The settler is a tool in service of Israel’s colonialism goals. He [the settler] is the one that is doing the job for them. So, for sure, he should feel supported in order for Israel to be able to build outposts and confiscate Palestinian land. Whenever the settlers call for the army, the army will show up and listen to them. The difference between how the Israeli government treats us as Palestinian and how it treats the settlers is clearly very racist.

There are also legal supports. Like, if a settler attacks Palestinians, as we have witnessed, most of the time when the policeman come to the field, “First of all, go file a complaint in the police station” [located in the settlement of Kiryat Arba, but Palestinians looking to file a complaint, must drive around the settlement, into Hebron, and enter from the Palestinian side].

We should also compare how the Israeli forces treat Israeli or Jewish solidarity activists versus the settlers. For example, a few days ago, settlers from an illegal outpost attacked Israeli and Jewish activists from the group that you were a part of. One settler choked an Israeli activist [Itai Feitelson], pushed him to the ground, and stole the phone of another Israeli activist [Yasmin Eran-Vardi]. Everything was filmed.

Maybe if this happened inside Israel, maybe the two Israelis—Israeli settler and the Israeli activist—would be treated the same based on the law. But in this case of a clear physical attack, the settler, whom the Israeli activists filed a complaint against, was banned from the area for 10 days, instead of going to jail or doing something for the Israeli activists.

So the treatment of these different groups is just based on who is the favored person who will be used as a tool by the Israeli authorities in achieving its colonialism in the occupied Palestinian territories.

The Israeli High Court ruled less than two weeks ago that the army has the green light to immediately forcibly remove over 1,000 residents of Masafer Yatta because the Israeli army claims that it needs the territory as a live-fire training zone. And I want to quote from an article by Amira Hass in Haaretz, where she explains a little bit about the judges’ reasoning behind their May 4th decision. “The justices dismissed disparagingly the evidence provided by the residents – oral testimony, documents and physical evidence from the actual area – attesting to their connection to the place, past and present… The justices adopted with enthusiasm the position of the state, which held that the residents of Masafer Yatta had invaded the area only after the army declared it a training zone in 1980. In other words, according to the State Prosecutor’s Office and the High Court, a population of farmers and herders, who lead very simple lives, plotted in bad faith to prevent the area from being turned into a military training ground, choosing to live in a place without running water, electricity or paved access roads, without the right to build.” How do you respond to the high court's claim that you and your parents and your grandparents plotted to only occupy this area after the declaration of the firing zone?

The Nakba and the 1967 occupation by Israel did not force us to move from another part of Palestine to this one. In 1942, before the creation of the State of Israel, my grandfather was born in Tuba, in Masafer Yatta. My family has been living all our lives in this area ever since. And my grandfather bought the cave where my family currently resides directly after he got married in the late 60s.

The first attack by Israel against Masafer Yatta was committed in 1966, in a village called Jinba, one of the villages now facing imminent evacuation by the Israeli army. I just recently met a person from Jinba who was born there in 1962. He told me about how in 1966 the Israeli army destroyed people’s houses.

And if you look at the kinds of jobs that people in Masafer Yatta have, you will understand that they have been living here a long time. The people here are not engineers or doctors that could live in the city. The shape of the land imposes how a person will keep up with this area. All people here are shepherds and farmers. And they have been living with this work as their only income all their lives.

Israel would make the lie and then believe it. Ariel Sharon, who is a former Prime Minister of Israel [then Minister of Agriculture], said it himself in the Settlement Affairs Committee, when he suggested offering Masafer Yatta as a training zone for the Israeli army. He said that he wants to hold us [Palestinians] from the mountains to the deserts. And then he declared the firing zone when he became the Minister of Defense. Israel declared our homes as a firing zone.2

What is the strategy that you and other Palestinian leaders from Masafer Yatta are going to use in order to respond to this court decision and to plan for what the Israeli military may do today, next week, or a year from now?

We as Palestinians never expected justice from the court of the occupation. This Israeli High Court of Justice appointed a settler to look at our case. The decision ended 22 years of our lawyers giving the proofs that we are permanent residents of the area and that Israel is violating international law with this forced transfer. In the end, the court ruled in favor of the army and for our evacuation.

Decades of asking for justice from the occupier really exhausted us. It proved to be useless—decades of showing that this is my only home, that I have no other place to go, that you are committing a war crime against us. In the end, the court doesn't care and is ruling in the favor of the army. You could have done so 22 years ago. Why did he do it now? What was your intention after he [the court] evacuated me from my home in 1999? You made me wait for 22 years, and then rule the same way [for evacuation]? I was there and I was coming to tell you that there is a home demolition against me in my village. I was there and your army was demolishing the barns of my sheep, and the water systems that I built for my children. And then you ignore everything. And you see the whole process of demolition against the people's properties in Masafer Yatta. So there is no expectation of justice by Palestinians from the occupation court.

Our only hope now is for the international community to pressure the Israeli government and Israeli Ministry of Defense. We are trying, first and foremost, to take action on the ground in order to raise awareness and also campaigning so that Americans will write to their congressmen in order to send diplomatic letters to Israel asking the government to stop the evacuation of the villages. Masafer Yatta is maybe the biggest community that Israel has attempted to evacuate since 1967. But it is not the first. Just one a few kilometers next to us, in the same area of Masafer Yatta, in the South Hebron Hills, the Israeli High Court of Justice ruled in favor of the evacuation of the village of Susiya. But Susiya is still there today because the Congress pressured the government of Israel. Same situation with the village of Khan al Ahmar, as well as other Palestinian villages around.3

We are staying here. Whatever will happen, we are not leaving our homes.

We've been talking about state violence. We've been talking about so many experiences that you and other Palestinians in Masafer Yatta and across historic Palestine have of being victimized by settlers and the military. I wanted to move away from that victimization to ask you, what makes you feel powerful? What makes you feel strong?

People like you, Zak. The only thing that makes me powerful are all the people around me. My neighbors. Whenever we face, for example, an attack by the settlers or the army in our village, we see all of us standing together in order to stop this aggression. By myself, I would not be able to do it. Our power comes from the people standing together to stop this violence.

I also draw power from the different people all around the world who support our struggle. I have met and talked to hundreds of people. Hundreds more follow me on social media and take action against the occupation. It gives me hope that people from the United States, such a long distance away, are taking actions in order to stop the evacuation of my home, Masafer Yatta. So, for sure, this gives me hope and gives me power.

I was volunteering alongside you in the South Hebron Hills for three months with the Center for Jewish Nonviolence. You're a committed nonviolent activist. I wonder why you choose nonviolent resistance. You choose journalism and storytelling and international advocacy. Why not take up arms against the settlers and the army that occupies you? It's your right, isn't it? Why choose nonviolent activism?

First of all, because I don't want to hurt other people. I'm just trying to say that, "I have the right to live." I don't want to hurt any other human beings in this world. Like, even the settlers and the military who are depriving me of the main elements of life—I don't hate them as human beings.

Any people under the occupation, as you said, have the right to resist in any way they believe. I believe in the nonviolent resistance because we have a long history of Palestinians resistance against the Israeli occupation and we have seen the response of the Israeli military to people who do armed resistance: Either they will be killed, or they will spend their whole life in jail. And I don't want this. I don't want to be killed. I don't want to spend my life in jail. I want only to defend my rights in the way that doesn't hurt me. I want to live. I am a master's student. And I wish to remain free with my loved ones. So I would choose another way to resist the occupation. The occupation’s main goal is to evacuate me from my own land, and I don’t want to give them an excuse to do so, to erase me from the surface of the ground—if that’s an expression.

What’s it like working with Jewish people? We hear all the time from Israeli political leaders that there's no partner for peace on the Palestinian side. I'm wondering: do you see a partner for peace, or partners for peace, on the Israeli side, on the Jewish side?

My problem is not with Jewish people. My problem is with the occupation of my land. I am ready to partner with any person, whether they’re an international, an anti-occupation Jewish international, or an Israeli against their own government, so long as they’re willing to work together to end the oppression of the occupation of the Palestinian people.

How do you understand the term Zionism? What does Zionism mean as you understand it? When someone says, “I support Zionism,” or, “I oppose Zionism,” what is it that they're supporting or opposing? What does it mean to you?

“I support Zionism” means supporting expelling me from the borders of historical Palestine.

Are you an anti-Zionist?

[Chuckles] Of course I am anti-Zionist.

The head of the Anti-Defamation League, Jonathan Greenblatt, said that if you are anti Zionist, that means that you're antisemitic and basically you're the same as the white nationalists in America, the people who are marching in the streets, saying, “Jews will not replace us,” who believe that Black people are a lesser race. Anti-Zionists are just the left-wing version of these right-wing bigots. What do you think of that?

From my point of view, if you are Zionist, you are antisemitic. Using Judaism to violate other people’s rights is antisemitic. For me as a child living, in Masafer Yatta, because of the violence against me from the Zionist settlers in my area, the symbols of the Jewish people (the kippah and everything) became for me the symbols of the terrorism. When I grew up and met anti-Zionist Jewish activists showed me that Judaism is not Zionsim.

I can tell you that in the American Jewish community, we understand a central part of our Jewish identity to be about social justice.

When I heard Greenblatt say that anti-Zionists were the “photo inverse” of white nationalists, I could only think about my experiences with settlers from the outposts that we've been talking about, and how, to me, those settlers actually resemble the white nationalists better than anyone else.

How do you envision Palestinians and Jewish people existing in the Land after the occupation ends? And then, specifically, what do you plan to do the day after the occupation ends?

Today is May 15th, 2022, which marks 74 years of Palestinian oppression. First, for decolonization, we must welcome back the six million Palestinian refugees who are now living outside the borders of historical Palestine. They have the right to return to their homes.

Talking about Jews and Palestinians in this Land, we must recognize that decolonization would be related to Zionism. Jews and Palestinians really were living here together, side by side, before Zionism. Zionism has ruined everything by convincing Jewish people that building their national home required Palestinian oppression. In 1948, 700,000 fled from Palestine because of the massacres perpetrated by Zionist gangs against Palestinians and the hundreds of Palestinian villages that were destroyed. But before that, Jews and Palestinians had the experience living together away from politicians and the threat of winning versus losing. I’m sure that they can do it again with full justice and equality for everyone.

On the day after the occupation ends, I would like to drive my car through the road that used to lead to my village, where there is an Israeli outpost today. Since I was born, I have never been able to walk on this road. I would love to walk with my family on this road, because this road used to lead to my village and now Havat Maon is built on it and we are not as residents able to use it anymore. I want to feel what it’s like to use this road without the threat or fear of attacks by the settlers.

Grazing in the land near my home today is very difficult because of threats of attacks from the settlers and arrests by the army. I want to see what it feels like when I can leave my family flocks grazing on those hills next to the outposts without really having any fear. Our dreams are simple, Zak. We are just trying to live in peace.

(Once again, if you would like to support Ali and thousands of other Palestinians from Masafer Yatta in their struggle against imminent forced removal, please write to your U.S. Representatives and Senators immediately.)